Background

Martin Suckling, composer

Music-for-games: this is familiar. But what about games-for-music?

Reverse the relationship. Let the game serve the music. What happens when music leads, when it is released from the demands and conventions tied to a visual experience? The support for branching structures and spatial audio and that are built into game engines offer a new way of writing and encountering sound, where the music is composed but still malleable, where it can respond, nudge, mould itself to the player’s actions, where the listener becomes the performer.

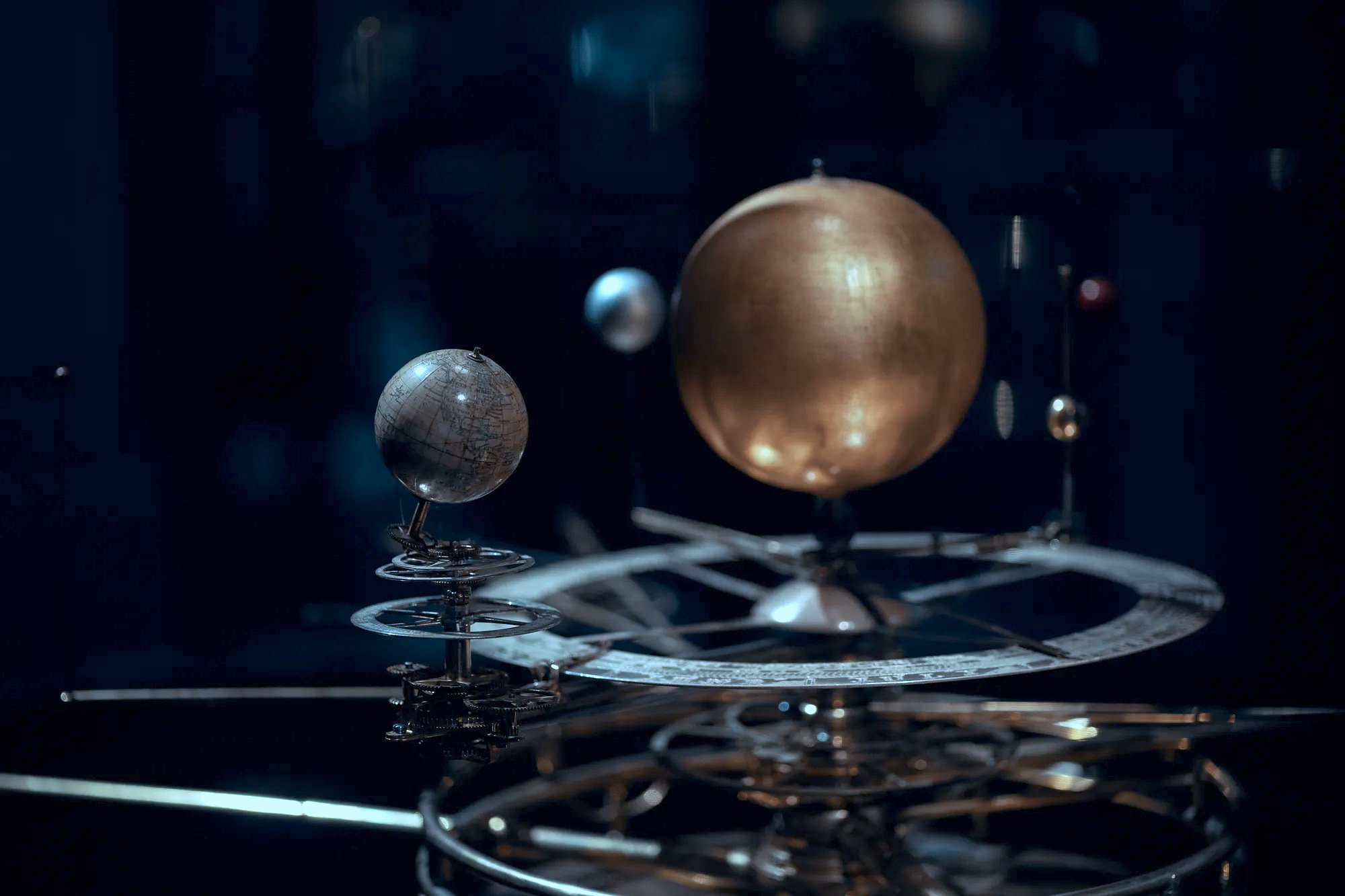

I wanted to write a piece that would take advantage of these opportunities, something to be encountered online that would make sense of online as a ‘venue’, something with which you can actively engage, where your choices affect the music you hear – and where this approach allows you to navigate a story by ear. I imagined a game-world like an enormous orchestra surrounding you, where as you walked between the players the sound would transform from music to music depending on where you were.

Happily, Digital Creativity Labs were also enthusiastic about the idea of combining aspects of ‘choose your own adventure’ with contemporary opera as a story-in-song, and so with their support and software development expertise, Black Fell became a reality.

Initially, the intention was to create an entirely audio experience, without any visuals to distract from the music, the darkness corresponding to the starless night in which the story is set. The intense aural focus required to make sense of this environment was immersive, but could also be disorientating, leaving the connection between player movement and sonic result uncertain. A variety of visualisations were therefore developed to help guide the player – a forest, standing stones.

Embracing non-linearity in music and poetry brought many challenges. Frances handled the literary ones with characteristic finesse. (Why should a story branch? Why should we want to encounter it multiple times? How can the endings be commensurate? What sort of language and poetic structure is appropriate?)

The musical challenges are no less thorny. How to write music which is complete with a single layer, but has space for multiple additional layers? How to ensure everything makes sense harmonically? How to manage metre when timings depend on player actions? How to communicate the generation of musical structures to a software developer such that they can be coded into the game environment? What sort of notations are meaningful for this sort of music? And so on and so on.

Alongside the branching possibilities present in most interactive fiction, the music-based game environment enables a new element: a ‘thickening’ of the branches. For each fragment of text there is a range of music that can be associated with it, and this music can occur in different combinations and balances and sequences, all depending on the player ‘following their ear’ to the sounds they prefer. So as well as there being many paths to travel down, you encounter these paths in constantly changing conditions; though you can choose the same route twice it will never sound the same. For us this matched the core idea of the text, a process of circling around memories, a self-excavation of buried thoughts and changing emotional colouration as one replays and reintegrates past events in one’s mind.

Is it a game or an opera? It’s both. You don’t play to win, but you do play it as you listen. A game-for-music.